The Wyoming Sheep Business

By

Samuel Western, www.wyohistory.org

“There seems to be no doubt that the vast quality of mutton can be grown here, pound for pound, as cheap as beef; and, if so, then sheep-raising must be profitable if cattle-raising is.”

—Silas Reed, surveyor general of Wyoming Territory, from his report for 1871.

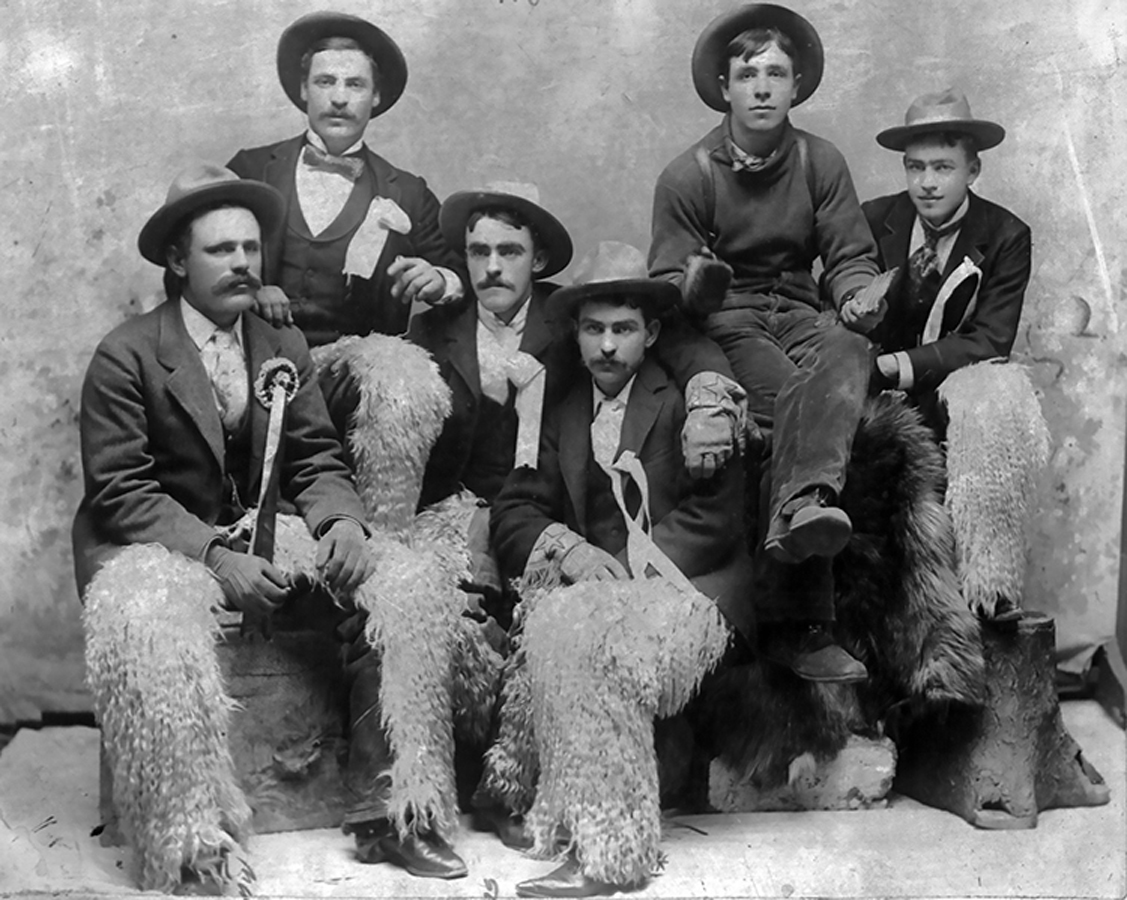

Sheep ranching in Wyoming or the West simply never earned the same cachet as running cattle. When historian Frederick Jackson Turner, in his famous Significance of the Frontier in American History essay, describes “the progression of civilization” marching past Cumberland Gap, he mentions “buffalo following the trail to the salt springs, the Indian, the fur-trader and hunter, the cattle-raiser, the pioneer farmer”—but doesn’t say a word about sheep. Still, many a savvy 19th century Wyoming flockmaster made a great deal of money in the wool, lamb and mutton business.

It took a while for the notion to catch on: The eastern states and Ohio raised most of America’s sheep. Small numbers arrived in Wyoming as early as 1847 but they, like their owners, were transient. According to Levi Edgar Young’s The Founding of Utah, a Mormon pioneer company that left Omaha in July 1847 and arrived in Salt Lake City on September 19 included 358 sheep.

During the Civil War, high demand for wool for uniforms led to high prices, which encouraged production worldwide. The global supply of wool increased more than a third between 1860 and 1870; a large part of the gain occurred in the first half of the decade due to the cotton famine.

After the war, demand plummeted and prices crashed. According to a report from the American Historical Association, sheep production after the war, between 1867 and 1871, fell by 75 percent in the mid-Atlantic states and by 25 percent nationwide.

This meant that people who wanted to make money in the sheep business had to be low-cost producers. This drove sheep production west, where grass was free on the public domain.

Early Sheepmen

The sheep industry in Wyoming had modest beginnings. In 1870, for example, Thomas Durbin brought 900 Mexican sheep – Churros – into Cheyenne for the purpose of turning them into mutton. He ended up breeding them instead.

Edward Creighton had contracted to build telegraph line through what are now western Nebraska and eastern Wyoming in 1861, and ended up running 10,000 sheep in both territories.

In 1873, cattle and sheep operators in southeastern Wyoming Territory formed the Laramie County Stock Growers Association. The purpose was “to advance the interests of stock growers and dealers in livestock of all kinds within the territory.” It wasn’t until 1879 that the cattlemen and sheepmen parted ways. The tension between them increased as sheep numbers increased and, eventually, free grass became scarce. The Wyoming Wool Growers Association did not form until 1905.

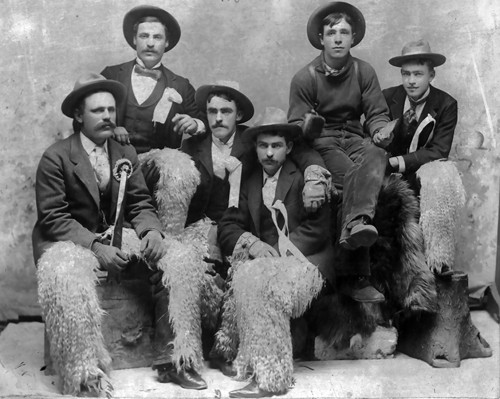

During the 1870s another important figure entered the sheep business: Francis E. Warren of Cheyenne. Storekeeper, rancher, territorial governor, briefly state governor and finally U.S. senator for nearly 40 years, Warren owed much of his wealth and power to sheep. A U.S. Senator from Iowa called Warren “the greatest shepherd since Abraham.”

The ascent of the sheep business differed from the cattle boom. Wholesale prices for cattle doubled from 1878 to 1882. From 1881 to 1885, cattle prices rarely slipped below $5 per hundredweight. Sheep prices were more stable. Though they enjoyed strong months, prices stayed between $3.50 and $4.50 per hundredweight until the disastrous winter of 1886-87. At the same time the price of wool, remained flat or slightly declined.

Wyoming operators like the Cosgriff Brothers–Thomas, James and John – did run sheep, however. These three ex-Vermonters purchased land between Hanna and Rawlins, Wyo. from the Union Pacific Railroad, and eventually built their flocks to 125,000 head. They entered the business in 1882.

Producers began importing bands as large as 10,000 head—from the West Coast. In 1882, Hartman K. Evans and his partner, Robert Homer, drove 23,000 sheep 850 miles from Pendleton, Ore., to Laramie, Wyo. It took them four months.

National production was growing steadily, and much of the growth must have been due to sheep in the West. The wool clip, or total supply of wool, increased in the United States from 264 million pounds in 1880 to 329 million in 1885, or roughly 25 percent in six years.

Economic Adversity

But trouble came. Besides avoiding clashes with cattlemen about grazing, Wyoming sheep operators had to survive three calamities in the next 15 years: the killer winter of 1886-1887, which reduced herds and ravaged prices; a financial earthquake, the Panic of 1893; and the Wilson-Gorman Tariff of 1894, which eliminated the import duty on wool and created a dreaded “free wool” era.

Warren, for example, managed to make it through the winter of 1886-1887, and by 1890 was running 110,000 sheep and his lamb crop reached 25,000. Yet the Panic of 1893 spared no one; it bankrupted even the Union Pacific Railroad. In 1894, the Warren Livestock Company went into receivership as well, with $200,000 in debts. Wyoming wool revenue in 1894 was roughly half of what it was in 1890.

The Cosgriffs apparently survived the Panic. In 1895 the brothers sent the largest shipment ever of Wyoming wool– 800,000 pounds—via that same bankrupt railroad to Boston.

It’s not surprising, therefore, that Warren testified before Congress in 1894 that Wyoming could not survive without a wool tariff. “We cannot compete successfully in any part of the United States with Australia in raising wool,” he said, noting that the state’s production costs were too high. “The condition of sheep and woolgrowing is very severely depressed, more so than any other business in the State and growers are greatly discouraged,” he added.

The lack of federal support for wool did have one silver lining: Producers began raising more lamb and mutton. Previously, sheep—most of them Merino or crossbred Merinos —were raised for their wool. Now Rambouillet, Shropshire, Cotswold and Delaine Merinos—a breed created for wool and meat production—were being introduced into herds and making sheep dual-purpose animals.

The Dingley Act

Warren had a strong affiliation with the American Protective Tariff League, one of the leading anti-free trade organizations of the day. The Wyoming senator chance to support Congressman and fellow Republican Nelson Dingley, Jr. of Maine and his Dingley Act, which doubled any historical tariffs on wool.

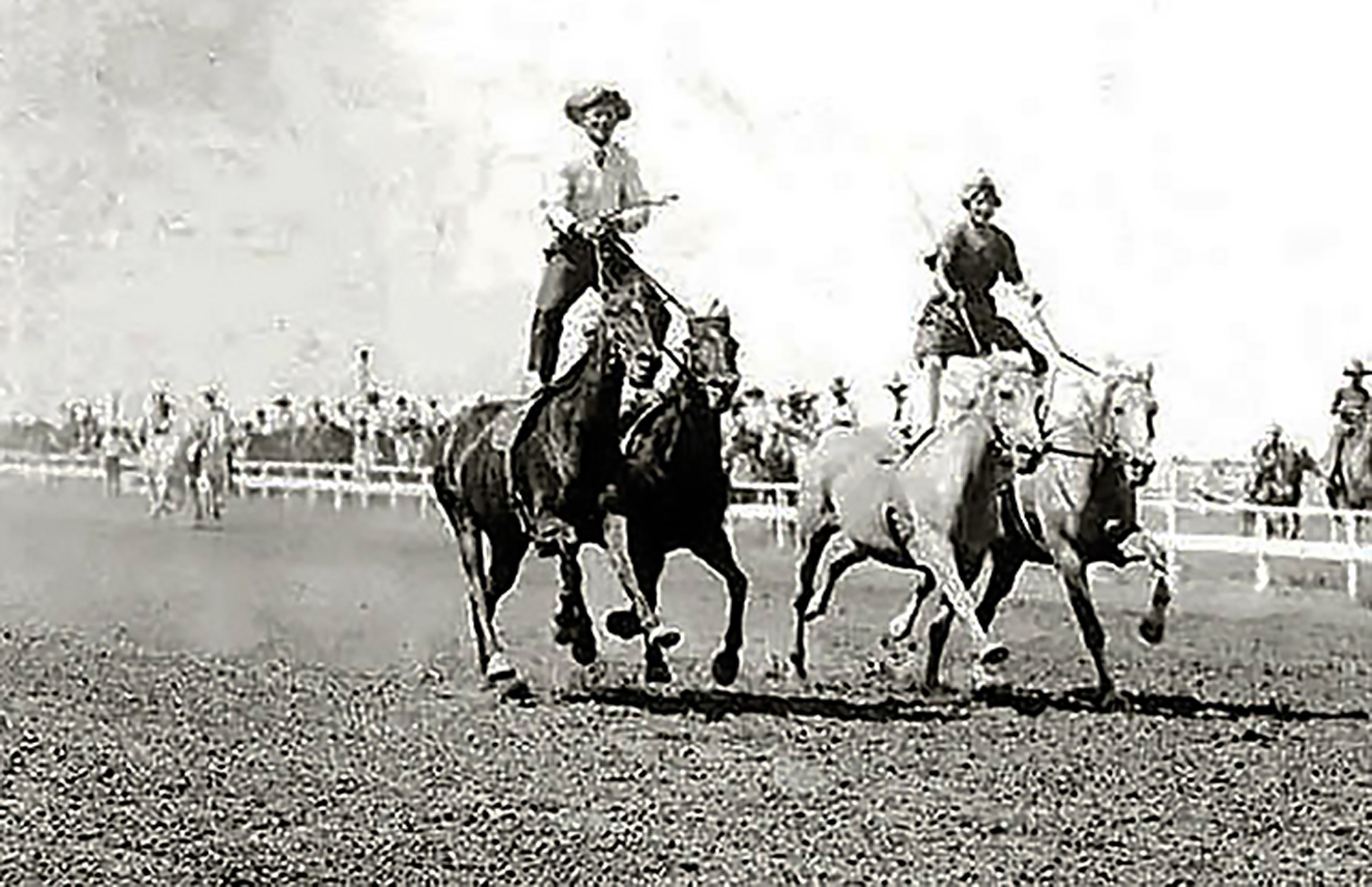

The Dingley Act of 1897 started a second boom in sheep. By 1890, there were 712,500 sheep in Wyoming. By 1900, Wyoming sheep had passed the 5 million mark. As for cattle, Wyoming counted 1.5 million of them in 1895 but by 1898, one year after the passage of the Dingley Tariff, there were only 706,000 head.

The ‘Bitterest War’

Given these fast-changing conditions, conflicts between cattle and sheep growers were perhaps inevitable. They centered on grazing rights on the public range. As Frank Benton, a writer and cattleman from Eagle County, Colo., wryly wrote, “a sheep [has] no business eating grass away from a steer.” Violence against sheepmen occurred all over the Rocky Mountain West, but the battle in Wyoming, notes America’s Sheep Trails author Wentworth, was “the bitterest war of all.”

The acrimony began early. Edward Smith, a banker with Beckwith-Gwynn and Company of Evanston, Wyo., testified before the 46th Congress (1879-1881) that “the law of the Territory…prevents trespassing on occupied ranges near settlements, but away from the settlements the shotgun is the only law, and sheep and cattleman are engaged in constant warfare.”

With the passage of the Dingley Act in 1897, the dam holding back cattlemen’s resentment burst, and no part of Wyoming was spared. The Bighorn Basin in particular endured more than its fair share of troubles. One of the most violent acts happened in 1905 on Shell Creek in Big Horn County. A group of masked riders rode into Louis Gantz’s camp and shot, dynamited or clubbed to death 4,000 sheep, shot horses and burned the herder’s sheepdogs alive.

Five years later, In April 1909 on Spring Creek, south of Tensleep, Wyo., armed men approached a sheep camp and killed three men, roasting two in the sheep wagon and shooting the third—and killed the dogs.

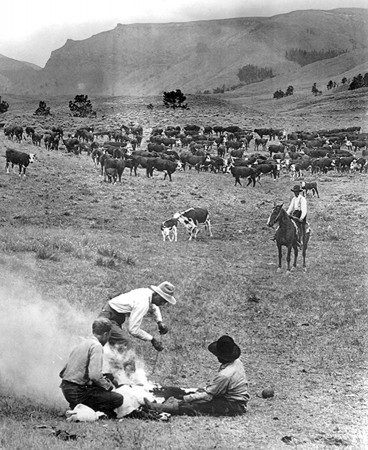

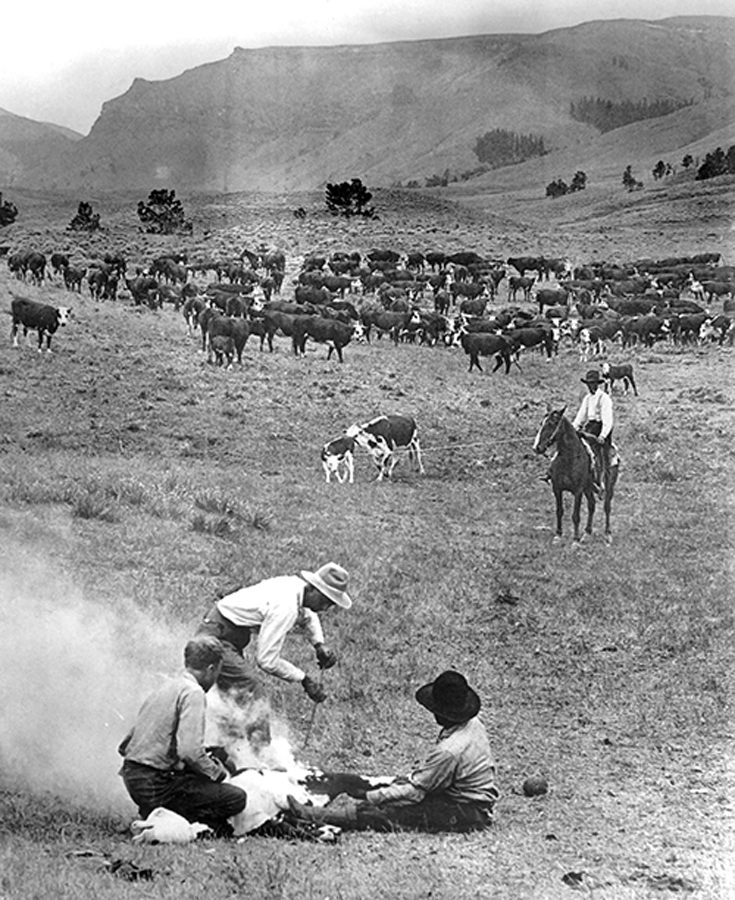

Despite this, herds expanded. By 1908, Wyoming led the nation in wool production with over six million sheep valued at $32 million. Wool topped beef, even in value. The value of cattle in Wyoming in 1910 was estimated at $26.2 million, according to a 1913 supplement to the 1910 U.S. Census.

A long decline

The acme was short-lived. By 1914, the number of sheep in Wyoming had been cut by 40 percent. A new tariff law, the Payne-Aldrich Tariff Act, was passed in 1909, but it was not, as some have claimed the replacing of the Dingley Act that caused the decline. According to Chester Whitney Wright, “the [new] act [of 1909] as finally passed made no alteration in the duties on raw wool as fixed by the Act of 1897.”

The cause was more systemic in nature. Cheap grazing land was disappearing. In 1906, the National Forest Preserve, which would soon become the U.S. Forest Service, began delineating grazing areas and charging five to eight cents per head of sheep to graze them seasonally on federal forest land.

Grangers were taking up land that formerly had been grazed by the flocks. In 1909, Congress passed the Enlarged Homestead Act. This legislation doubled the amount of land deeded to each homesteader from 160 acres to 320 acres. The Stock-Raising Homestead Act of 1916 doubled homesteads again, to 640 acres. In 1920, dryland farmers, homesteaders and ranchers filed for a record 3.9 million acres of land in Wyoming.

That grazing areas were saturated with livestock didn’t help. Finding grass for millions of ruminants pitted flockmaster against flockmaster. The Rock Springs Grazing Association formed in 1907 for the express purpose of preventing nomadic sheepherders from Colorado or Utah from using Wyoming’s winter range.

Public sentiment against woolgrowers took on an ugly tinge. “Sheep,” wrote G.W. Ogden in a 1910 article, The Toll of Sheep, “are by nature creatures of the desert. The lack of water for a week is no hardship to them. So they ravage like caterpillars, leaving nothing for the cattleman who trails behind, or who has depended for winter pasturage on the invaded land.”

Already by the 1910s, wool and lamb prices had begun a long decline, although there were brief periods of prosperity. World War I drove up wool and lamb prices and then dropped them flat. In 1919, a whole lamb on the hoof in Wyoming could be bought $3.

Finally, in 1934, the Taylor Grazing Act put an end to the old free-grass system that allowed nomadic flockmasters to graze their sheep wherever they could. Similar to the practices adopted on the national forests in 1906, the Taylor act imposed a system of land leases and per-head grazing fees on the unclaimed public land remaining in the West. Sheep growers now needed to own at least a small piece of private land if they were to graze their flocks on specifically designated, public-land leases.

Sheep numbers in Wyoming hit nearly four million during World War II, but that was the last hurrah. In 1984, Wyoming’s sheep population fell below one million. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, in 2011 Wyoming sheep numbered only 275,000, not even as many as Okie, Warren and the Cosgriff brothers owned in total in 1890.

With the decline of the cattle industry, many large cattle companies converted to wool growing. Among them The Spur, the Swan Land and Cattle Co., Ltd., the owner of the famed “Two Bar” in Chugwater, and the Warren Livestock Company. Foremost among the sheep breeding outfits was F. S. King Brothers in Albany County, located near the headwaters of the Chug in eastern Albany County was noted for its breeding stock stock which was sold internationally.

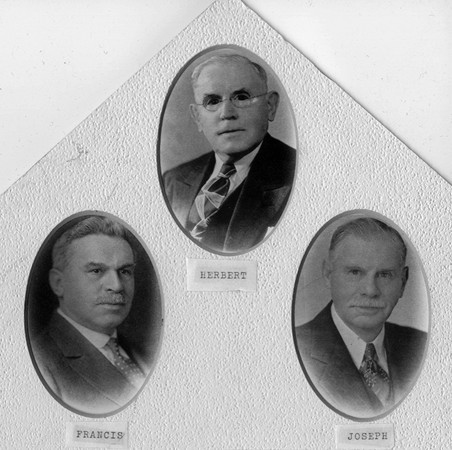

The King Brothers Ranch was founded by Francis Stocker King (1867-1933), the son of a Methodist minister. King emigrated to the United States from Britain in the late 1870’s. In 1884 King joined with Paul Pascoe. In 1885 he participated in a winter drive of sheep to Nebraska. On the drive two sheepherders froze to death, but King completed the drive. In 1888 he was joined in Laramie by his brother Herbert J “Bert” King. In 1891 a third brother Joseph H. “Joe” King came from England. In 1892, the three brothers began their own operation on Frank’s homestead. Frank and Joe cut the logs and with the help of a carpenter constructed the original homestead themselves.

The ranch grew from its original 160 acres to at one time holdings of 120,000 acres. and as the ranch the original homestead grew. The brothers turned from range stock to breeding stock purchasing top sheep.

The ranch was incorporated in 1904. The Brothers’ sheep repeatedly won grand championships at the Chicago International Stock Show, St. Louis and San Francisco. In 1914, F. S. King traveled to New Zealand and Australia at his own expense in search of better stock which would combine good characteristics for wool as well as meat production. In New Zealand he discovered on the Corriedale Estate a breed which met both requirements. Thus, he is credited with introducing the Corriedale sheep to the United States.

In 1916, F. S. King withdrew from the Laramie operation selling his interest to his two brothers. He then established his own operation, the Wyoming Corriedale Sheep Company. Following World War I, there began a slow decline in the production of sheep and wool in the United States. King explained:

“The summer of 1919 was one long to be remembered: drought was universal throughout Wyoming and in the fall at least one-third of the livestock had to be shipped out of the State. The remaining herds compelled the purchasing of hay and grain at prices that were appalling. Winter started from a month to six weeks earlier than the average and in October snow covered the State. Long cold months followed, ending with an April storm that has been unequaled since the March storm of 1878. This resulted in the loss of about two-third of the stock of the state and in many cases the cost of carrying though the winter was more than the sheep were worth in the spring. On top of this calamity came the depression in prices and sheep and wool were among the first to feel its effects. In a week wool fell from 80 to 25 cents and sheep from $18.00 to $12.00 down to $3.00.”

Following, Frank’s withdrawal from the original operation, Frank formed his own separate sheep breeding operation near Cheyenne, the Wyoming Corridale Sheep Company. His son, Arthur joined him in the business. At age 12 Arthur at the National Wool Growers’ Association won first place beating out his own father. Arthur was followed in the business by his son Jerry King. That operation sold its last Corriedale sheep in 1968 and converted to cattle.

The original F. S. King Bros. operation continued until the youngest of the original brothers, Joe died in 1949. The flock was dispersed and the original ranch was sold the following year. One hundred sixty acres have now been designated as an historic district on the National Register.

- S. King served in the State Legislature for twelve years and served as Grand Master of the Wyming Grand Lodge of the Masons. and also served as Grand Master of the Wyoming Masonic Grand Lodge.

The Sheep Wars

The Sheep Wars, or the Sheep and Cattle Wars,refers to a series of armed conflicts in the western United States which were fought between sheep men and cattlemen over grazing rights. Sheep wars occurred in many western states though they were most common in Texas, Arizona and the border region of Wyoming and Colorado. Generally, the cattlemen saw the sheepherders as invaders, who destroyed the public grazing lands, which they had to share on a first-come, first-served basis. Between 1870 and 1920, approximately 120 engagements occurred in eight different states or territories. At least 54 men were killed and some 50,000 to over 100,000 sheep were slaughtered.

Wyoming and Colorado

The sheep wars in Wyoming and Colorado were exceptionally violent and lasted until well after the turn of the century. Like in Texas and Arizona, the cattlemen of Colorado were unwilling to share their pastures with the sheepherders, who were crossing into the state from southern Wyoming. In Wyoming alone there were about twenty-four attacks and at least six deaths between 1879 and 1909, though other accounts say that over sixteen people were killed. The most well-known of the conflicts was the Routt County Sheep War, in which the cattlemen of Routt County, Colorado attempted to keep the Wyoming sheepherders from entering their grazing ranges. On May 23, 1895, the newspaper Cheyenne Leader reported that four days previously “riders were sent out to scour the country and warn the settlers that sheep men now holding their flocks on Snake River at the Wyoming line [border], were contemplating an invasion of the Bear River cattle ranges. The effect was electrical, and by noon today fully 350 cattlemen and feeders were assembled to decide upon positive action to keep the sheep back….” Shortly after that, the cattlemen adopted a series of resolutions that established deadlines and effectively banned all sheepherders from entering northwestern Colorado. However, the Cheyenne Leader reported that the sheepherders would most likely disregard the ban and enter the state anyway. To enforce the resolutions, the newspaper said, the “stock feeders and cowboys [cattlemen], with a force of eight hundred to a thousand are holding themselves in readiness forcibly to resist any advance made south of Hahn’s Peak by the sheep owners…. A war is imminent and unless the more conservative heads prevail, the rifle will figure a conspicuous part in a Routt County sheep war. The sheep that are causing the trouble are some sixty thousand head belonging to J. G. and G.W. Edwards and others in Wyoming.”

Despite the newspaper’s claim, most of the sheepherders respected the cattlemen’s resolve, which defused the situation before it became too serious. There were, however, at least four violent episodes in the region during the time. The first occurred in 1894, in Garfield County, when 3,800 sheep were driven over cliffs into Parachute Creek. The sheepherder, Carl Brown, attempted to stop the cowboys from killing the flock but he was shot in one of his hips. When a posse from Parachute, Colorado rode out to the scene, they found the wounded Brown and a “mass of dead sheep at the foot of a 1,000-foot bluff.” The Craig Courier reported the following on September 14, 1894; “The owners [of the sheep] are residents of Parachute with rights to the adjacent range and the posse made a futile race to apprehend the raiders. John Miller owned seventeen hundred of the sheep and Charles Brown, uncle of the wounded man, twenty-one hundred.” About 1,500 more sheep were also massacred the same year in the same county.

According to Jack Edwards of Wyoming, in late June 1896, two of his sheepherders were killed by Colorado cowboys and 300 of his herd were massacred. Upon learning of the raid, Edwards headed towards the scene but he was intercepted by a “party of masked men,” who ordered him to remove the rest of his flock back across the border. After the raid, on January 23, 1897, Edwards told an Omaha reporter the following; “I have an armed force of about fifty ready for the clash when it comes. I am compelled to keep a small army about my place all the time. A short time ago three hundred sheep were killed and two herders; for a while it looked as though the entire Colorado militia would have to be called out, but the sheepmen and cattlemen looked out for themselves, and there are several graves in the vicinity of Meeker that go to show that they know how to do this.” Another incident took place on the morning of November 15, 1899, when forty masked men attacked a sheep camp located on the lower Snake River. During the foray, over 3,000 sheep were “clubbed and scattered”, the shepherds were robbed and their wagon was burned.

Some of the more serious raids, outside of the northwestern Colorado area, occurred in 1887, 1896, 1902, 1905 and 1909. In 1887, nearly 2,600 heads belonging to Charles Herbert perished when some cowboys burned down his corrals at Tie Siding, Wyoming. In 1896 in Wyoming, about 12,000 sheep were slaughtered in a single night by being driven off a cliff near North Rock Springs. The violence reached its height after the turn of the century. In 1902, near Thermopolis, Wyoming, several thousand sheep were slaughtered and their herders killed. During the summer of 1905, ten masked men attacked a sheep camp on Shell Creek, in the Big Horn Basin. There the cowboys clubbed about 4,000 sheep, out of 7,000, burned the wagons and two sheep dogs. The owner of the massacred flock, Louis A. Gantz, lost about $40,000 as a result. Out of all the sheep raids, the most serious incursion was the Spring Creek Raid of April 2, 1909. Just southwest of Ten Sleep, Wyoming, the sheepherder Joe Allem and and two of his companions were shot and killed by seven or eight masked men. The raiders also killed about twenty-five sheep and two dogs, and burned the wagons with kerosene. Because sheep raiders had never

been prosecuted in a Wyoming court before, many believed that the murderers would get away with the massacre. However, seven men were eventually arrested, five of whom were sent to prison. The conviction of the Ten Sleep murderers brought peace to Big Horn County. After the 1909 attack, cattlemen were reluctant to raid sheep camps because now they risked being punished for it. Though there were two more Wyoming sheep raids in 1911 and 1912, no more sheepherders were murdered. The last known sheep raid in Colorado occurred eight years later, in 1920, when 150 sheep were slaughtered for grazing in the White River National Forest.

According to Robert Elman, author of Badmen of the West, the sheep wars ended because of the decline of open range land and changes in ranching practices, which removed the causes for hostilities. The Taylor Grazing Act of 1934 also eased some of the tension.

Samuel Western is a Sheridan-based freelance writer focusing on the economic and demographic history of the West and western communities and locavore food issues. His latest book, Canyons, will be released in August 2015 by Fithian Press (www.wyohistory.org)

Learn more about sheep ranching in Wyoming.