The Wyoming Cattle Boom, 1868-1886

By Samuel Western

It’s been often said that Wyoming’s cattle industry started by accident. That’s a bit of stretch, actually.

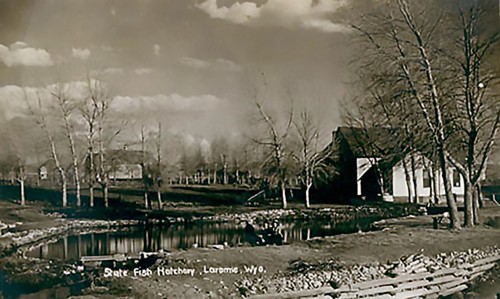

As the tale goes, Seth Ward, a sutler to Fort Laramie, left cattle out to graze the open range in the winter of 1852-53 along Chugwater Creek north of what is now Cheyenne. He expected to find carcasses in the spring. Yet when he returned he found “the oxen,” as he called them, thriving.

Popular history provides a series of similar stories: In 1854, Alex Majors, a freighter and provisioner, tried the same experiment in the same vicinity with considerable success; Mormons outside Fort Bridger also began leaving cattle out all winter.

The cattle boom of the 1880s created Wyoming’s indelible image as the Cowboy State. “The Roundup” by Frederic Remington, 1888. Wyoming Tales and Trails. These stories may be true, but they resist documentation. Alex Majors’ Seventy Years on the Frontier, for example, mentions nothing about wintering cattle in Wyoming. But historical veracity matters little in this case. Wyoming would have had a bovine boom even without the discovery that cattle could survive winters without supplemental feed. Between 1840 and 1870 a series of events combined to bring an inevitable surge of livestock to the northern plains.

As is so often the case in major economic shifts, a war—in this case, the Civil War—combining with changes in demographics and technology, laid down the foundation for a cattle boom.

It began with changing demographics. People were moving west. University of Wyoming historian Phil Roberts estimates that between 1841 and 1860, roughly 350,000 people “crossed what is now Wyoming.” As early as 1836, pioneers and freighters drove wagons over the Oregon Trail to Idaho. Mormons began passing through Wyoming on their way to Utah. A gold discovery outside Sutter’s Mill in California in 1848 vastly increased the traffic.

These new arrivals brought clashes with the Plains Indian tribes, primarily the Lakota Sioux, Arapaho and Northern Cheyenne. In 1849, to protect these emigrants, the U.S. government bought Fort Laramie, located near the confluence of the Laramie and North Platte rivers, from the American Fur Company for $4,000.

Seth Ward, sutler at Fort Laramie in the early 1850s, supposedly left cattle out to graze one winter along Chugwater Creek–and they survived. Kansas City Public Library, Missouri Valley Special Collections. Fort Laramie housed up to 350 soldiers, and they needed to eat. Provisioners like Ward and Majors obliged them by supplying beef to the quartermaster, thus establishing local demand.

At the same time, railroads began to revolutionize beef transport—both for live cattle and chilled, butchered beef. In 1851, the Missouri Pacific Railroad laid down the first tracks west of the Mississippi. Simultaneously, the New York-based Ogdensburg and Lake Champlain Railroad began shipping butter in refrigerated cars to Boston. In 1857, the first car of chilled beef left Chicago for eastern cities. It was a flawed system and failed. But the tinkering and improvements began.

Then there was the Civil War. This epic conflict left two enduring changes in the American cattle business: centralization of the beef-packing industry and a huge surplus (around five million) of Longhorn cattle in Texas.

Packing plants had been known in America since the late 1680’s when William Pynchon of Springfield, Mass., began packing cuts of pork and beef into barrels with brine. Still, the local butcher reigned supreme.

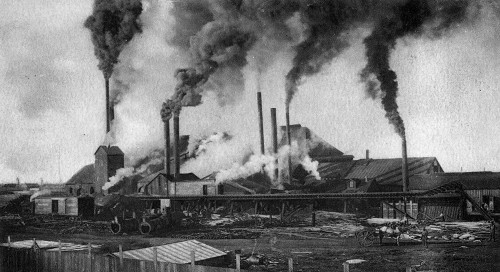

The Civil War brought on an unprecedented demand for first barreled and then tinned beef. Packers, now mostly in Cincinnati and Chicago, set up what they called disassembly plants, says Nebraska State Historical Society senior researcher, John Carter.

In a Nebraska Educational Television documentary, The Beef State, Carter explains, “You walked the animal in one end where it was greeted by an army of butchers who would slaughter the animal, cut it up, and actually developed a finished product – canned meat – which it would then sell to the government for the Union army. Now you had an industry that was producing food on a scale that could feed a nation.”

Paradoxically, while demand for beef in the East and the upper Midwest climbed during the war, it dwindled in Texas. By 1863, the Union Army controlled the Mississippi River, preventing the Confederacy from accessing Texas beef. Furthermore, young cowboys from the Lone Star State left ranches to fight for the Southern cause.

Untended, the herds grew. Supply soon outstripped demand. At the end of the war, a 3-year-old steer in Massachusetts sold for $86.00, according to an 1867 Department of Agriculture report. The same critter in Texas, probably a little leaner, went for only $9.46. Cattle buyer Joseph McCoy said of this era: “Then dawned a time in Texas that a man’s poverty was estimated by the number of cattle he possessed.”

New railroads, improved refrigerated cars and pent-up postwar demand for beef put an end to this dynamic. Among other things, the Civil War helped turn around a decades-old pattern of declining beef consumption. In a controversial thesis called The Antebellum Puzzle, University of Munich economic historian John Kolmos showed that American consumption of beef per capita declined steadily from the mid-1830s to around 1870.

If there was an accidental angle to Wyoming’s beef boom, it was geography. For example, the fact that railroad surveyors decided to route the Union Pacific through Cheyenne, not Denver, was much more influential in establishing a Wyoming cattle industry than a series of mild winters.

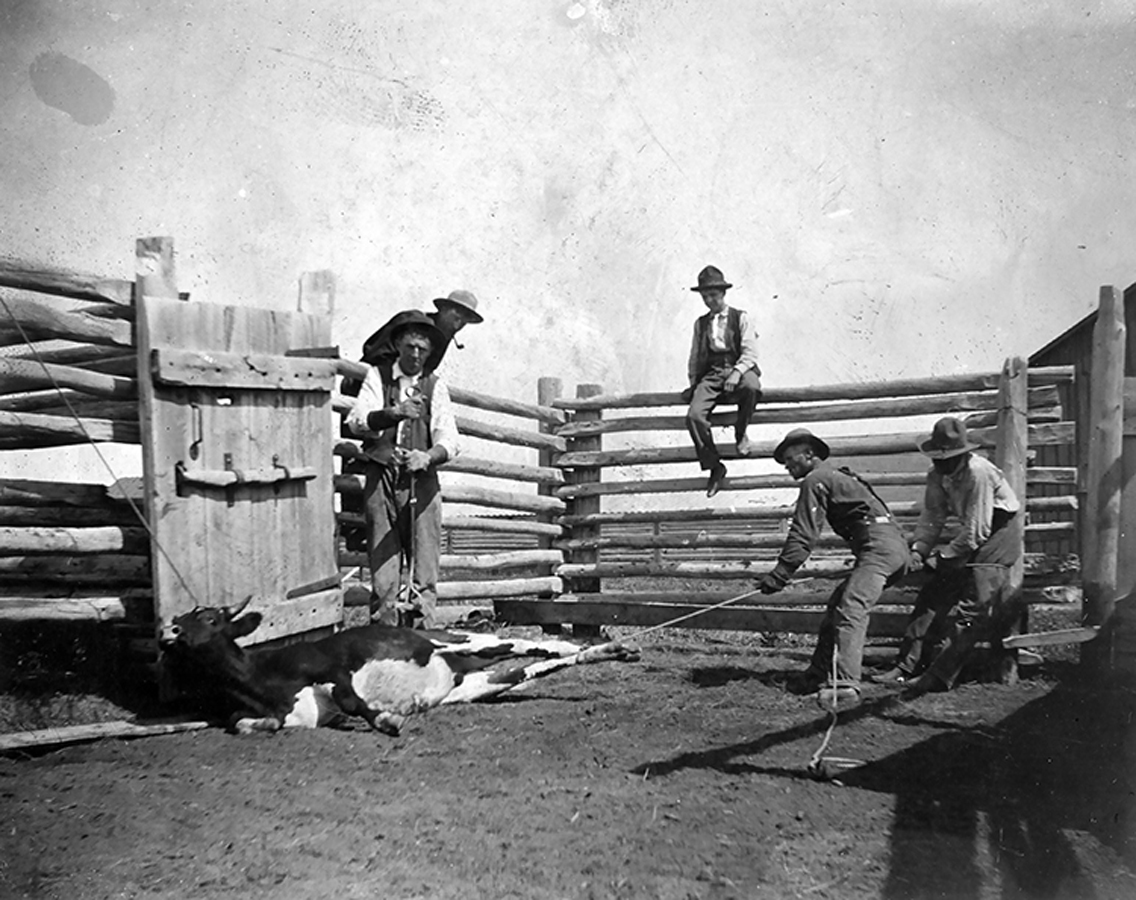

Nelson Story drove 600 head of cattle from Texas to Montana in 1867–up through the middle of what soon would become Wyoming Territory. Wyoming Territory was also handily located between Texas and Montana—the latter a site of various gold strikes. In 1866, Ohio-born gold miner and storekeeper Nelson Story, having made a bundle on a claim in the Alder Gulch strike outside Virginia City, Montana Territory, sewed $10,000 in greenbacks in his coat and headed for Fort Worth, Texas. He returned to Montana’s Gallatin Valley with 600 head of cattle.

That’s a journey of 1,500 miles, 450 of which were in what soon became Wyoming Territory. Even though Story and his men were attacked by Indians and harassed by the U.S. troops who forbade them to go farther on the grounds of safety, they made it to Montana. In the process, they got a good look at what’s now Wyoming—most of it open range with free grass–and the potential it held for future cattle production.

So, by the time John Wesley Iliff started a cow camp five miles south of Cheyenne in 1867 to supply Union Pacific railroad crews and the local Sioux tribe, Wyoming’s beef industry already had a foundation.

Then the boom really began.

*****

Among the most optimistic words ever to flow from a speculator’s pen came from Baron Walter von Richthofen, in his Cattle-Raising on the Plains of North America, published in 1885. “There is not the slightest amount of uncertainty in cattle raising.”

In this book, von Richthofen, who moved from the German province of Silesia to Denver in 1877, predicted cattlemen could count on profits of 156 percent over a five-year period.

The irony was that by 1885 the “beef bubble,” as historian and writer Helena Huntington Smith called it, had popped. People just didn’t know it yet. But in the early days such astounding profits were possible, especially in Wyoming Territory.

On May 1, 1867, Cheyenne Leader editor Nathan Baker spelled out the reasons for expected prosperity. Grass in Wyoming was abundant and “exceedingly nutritious.” Good water was “everywhere.”

Mild winters necessitated no feeding, declared Baker, and while an operator might expect winter losses to his herd of two to three percent, this was still more economical than buying hay for feed. And then there was the railroad, which provided “cheap” transportation to markets. (Historian Gene Gressley pointed out more recently, however, that for decades many a cattleman dissented from this opinion on Union Pacific freight rates.)

Cheyenne, after recovering from the economic shock of the departure of U.P. tracklaying crews, prospered. In 1871, an estimated 60,000 cattle grazed the prairie within 100 miles of town. Representatives from Chicago packing houses crowded the bar at the young city’s InterOcean Hotel.

Noted names in Wyoming stock raising—F.E. Warren, Joseph Carey, Charley Hutton and the four Swan brothers—arrived. Territorial governors invested in livestock. Cattlemen founded one of the most powerful political organizations in the West, the Wyoming Stock Growers Association, in 1872. The opulent Cheyenne Club, built by cattle money, opened in 1880. Under its mansard roof, oysters were shucked, wine flowed and, as club member and Anglo-Irish cattle owner Horace Plunkett wrote, “cordial drunks” abounded.

Demand for beef grew on both sides of the Atlantic. Technology in the form of efficient refrigerated rail cars and ships helped. In 1876, England imported only 1,732 tons of fresh beef. Two years later, the amount exceeded 30,000 tons, with roughly 80 percent coming from the United States.

Further increasing demand, the U.S. government continued to feed displaced Indian tribes. An 1879 Report of the Commissioner of Indian affairs reported that the federal government bought 11,311 head of cattle from ranchers in 1878 alone to distribute to various western tribes.

Stockmen fanned out across Wyoming Territory, staking out ranches in the Bighorn Basin, the Powder River Basin and the upper Green River Valley. Cattle kept pouring in from Texas and Oregon.

Outside capital flooded in as well. Wholesale prices for cattle reached a heart-stopping $6.47 per hundredweight in May 1870— meaning an 850-pound steer went for $55. Those already in the cattle business around Cheyenne and Laramie—the Lathrams, the Iliffs and the Dole brothers— made a killing. Investors were convinced that they, too, could repeat such profits.

The math was pretty compelling. According to Scottish-born writer, cattleman and Wyoming ranch manager John Clay, it cost about $1.50 to raise a range steer. There were marketing and shipping charges, certainly, but during an unheated market, you sold that same steer for $23.00; at the peak it sold for over $60.00 per head. A stockman could enjoy a net profit of $40.00 per head during good times.

Harper’s Magazine in November 1879 published a scintillating article detailing a theoretical three-year profit schedule for a southern Colorado cattle ranch that began with its herd numbering 4,000. By the third year, the owner was clearing $114,615 or about $2.5 million in today’s money.

Prices slipped a little but for most of the 1870s hovered between $4.00 and $5.00 per hundredweight. This was high enough to keep enticing investors. Prices dropped below $4.00 per hundredweight in 1880, but capitalists remain undeterred, and the boom mentality of “We’re going to have another rally very soon,” took over.

The markets obliged. In March 1881, wholesale prices per hundredweight passed the $5.00 mark and kept climbing. In June 1882, packing houses were shelling out over $7.00 per hundredweight, or more than $60.00 per cow. This, in turn, attracted more investors. Prominent historian of the American West W. Turrentine Jackson estimates that British interests invested more than $45 million in American cattle in the 1880s. Between 1880 and 1900, 181 livestock companies incorporated in Wyoming with an aggregate capitalization of $94,095,800.

In 1882, the six counties of Wyoming reported 476,274 cattle, worth nearly $7 million, on their tax rolls. Since, for tax reasons, many cattlemen were known for underestimating their herds, there may have been twice that number on the range.

Cheyenne reportedly had eight millionaires among its 3,000 residents in 1880 –1 out of every 375. The prosperous town built itself an opera house in 1882 and was one of the first cities in the U.S. to have electric streetlights.

Then the same magic concoction that brewed up the boom began to sour.

Demographics, again, showed muscle. People were no longer just passing through Wyoming to someplace else, they were staying. In 1870, Wyoming had a mere 9,118 people. By 1890, that number reached 62,555.

The Homestead Act of 1862, the Timber Culture Act of 1872 and the Desert Land Act of 1877, all of which offered government land for free or at very low cost, began to garner serious attention. Under all these laws, people filed claims and could qualify for title to the land—patents—after three to five years, provided they made certain improvements such as building a house, planting trees or bringing water to the land. In 1884, more people filed for land claims than in the previous 14 years combined. The free-range era for cattlemen, already dimming, was coming to an end.

There were too many cows. Wyoming historian T.A. Larson estimated that by 1886 there were 1.5 million cattle (about the same number Wyoming has now) on the range.

The weather turned crispy dry in the summer and iron cold in the winter. A drought that began in Texas in the summer of 1884 crept north. By 1886, eastern Wyoming and Montana were the driest in memory. By September of that year, some parts of Montana had received just two inches of rain.

In his annual report of 1886, the commander of Fort McKinney near Buffalo, Wyoming Territory, wrote, “The country is full of Texas cattle and there is not a blade of grass within 15 miles of the Post.”

The beef bubble popped. By November 1886, wholesale cattle prices in Chicago fell to $3.16 per hundredweight, half of what they had been in 1884.

The winter of 1886-87 was known as the “death knell on the range.” Snow came early and stayed.

On Jan. 14, 1887, temperatures in Miles City, Mont., bottomed out at 60 below zero. The Laramie Daily Boomerang of Feb. 10, 1887, reported, “The snow on the Lost Soldier division of the Lander and Rawlins stage route is four feet deep, and frozen so hard that the stages drive over it like a turnpike.”

Historians generally agree that Wyoming cattle losses during that winter tend to be exaggerated. Larson thought overall the state lost about 15 percent of its herd, although operators in Crook and Carbon counties lost roughly 25 percent of their stock.

John Clay wrote in My Life on the Range, “As the South Sea bubble burst, as the Dutch tulip craze dissolved, this cattle gold brick withstood not the snow of winter. It wasted away under the fierce attacks of a subarctic season aided by summer drought. For years, you could wander amid the dead brushwood that borders our streams. In the struggle for existence the cattle had peeled off the bark as if legions of beavers had been at work.”

The Wyoming cattle business never again achieved the stature it had from 1868 to 1886. Not until 1910 did cattle prices again reach $7.00 per hundredweight. By then, cattlemen faced serious competition from the sheep industry. The value of Wyoming sheep in 1909, $32.1 million, exceeded cattle’s $26.2 million. Wyoming had 7.3 million sheep but only 960,000 head of cattle. The state was ranked number one in the nation in both wool and sheep production.

The Great Depression, which lasted from 1920 through 1940 in Wyoming agriculture—twice as long as in the rest of the nation—put profound hardship on cattlemen. After World War II, the cattle business regained strength, but by then the growing mineral industry encroached on Wyoming’s image as a cattle state.

The memory of that cattle boom era remains remarkably resilient, however. Despite getting the vast majority of its revenue from minerals, Wyoming is still known as the Cowboy State. In the minds of the public – and some cattlemen – the era has never really gone away, but is merely hibernating, waiting for the right time to make a triumphant return.

Samuel Western is a Sheridan-based freelance writer focusing on the economic and demographic history of the West and western communities and locavore food issues. His latest book, Canyons, will be released in August 2015 by Fithian Press

Learn more about the Wyoming cattle boom and other great western trivia.